Abstract

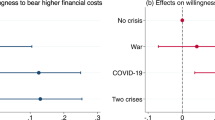

Mitigating climate change necessitates global cooperation, yet global data on individuals’ willingness to act remain scarce. In this study, we conducted a representative survey across 125 countries, interviewing nearly 130,000 individuals. Our findings reveal widespread support for climate action. Notably, 69% of the global population expresses a willingness to contribute 1% of their personal income, 86% endorse pro-climate social norms and 89% demand intensified political action. Countries facing heightened vulnerability to climate change show a particularly high willingness to contribute. Despite these encouraging statistics, we document that the world is in a state of pluralistic ignorance, wherein individuals around the globe systematically underestimate the willingness of their fellow citizens to act. This perception gap, combined with individuals showing conditionally cooperative behaviour, poses challenges to further climate action. Therefore, raising awareness about the broad global support for climate action becomes critically important in promoting a unified response to climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The world’s climate is a global common good and protecting it requires the cooperative effort of individuals across the globe. Consequently, the ‘human factor’ is critical and renders the behavioural science perspective on climate change indispensable for effective climate action. Despite its importance, limited knowledge exists regarding the willingness of the global population to cooperate and act against climate change1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. To fill this gap, we designed and conducted a globally representative survey in 125 countries, with the aim of examining the potential for successful global climate action. The central question we seek to answer is to what extent are individuals around the globe willing to contribute to the common good, and how do people perceive other people’s willingness to contribute (WTC)?

Drawing on a multidisciplinary literature on the foundations of cooperation, our study focuses on four aspects that have been identified as critical in promoting cooperation in the context of common goods: the individual willingness to make costly contributions, the approval of pro-climate norms, the demand for political action and beliefs about the support of others. We start with exploring the individual willingness to make costly contributions to act against climate change, which is particularly relevant given that cooperation is costly and involves free-rider incentives9. Using a behaviourally validated measure, we assess the extent to which individuals around the globe are willing to contribute a share of their income, and which factors predict the observed cross-country variation.

Furthermore, the provision of common goods crucially depends on the existence and enforcement of social norms. These norms prescribe cooperative behaviour10,11,12,13,14,15 and affect behaviour either through internalization (shame and guilt16) or the enforcement of norms by fellow citizens (sanctions and approval17). In our survey, we elicit support for pro-climate social norms and examine the extent to which such norms have emerged globally.

It is widely recognized that addressing common-good problems effectively necessitates institutions and concerted political action18,19,20. In democracies, the implementation of effective climate policies relies on popular support, and even in non-democratic societies, leaders remain attentive to prevailing political demands. Therefore, we also elicit the demand for political action as a critical input in the fight against climate change21.

Previous research in the behavioural sciences has shown that many individuals can be characterized as conditional cooperators22,23,24,25,26. This means that individuals are more likely to contribute to the common good when they believe others also contribute. We test this central psychological mechanism of cooperation using our data on actual and perceived WTC. Moreover, we investigate whether beliefs about others’ WTC are well calibrated or whether they are systematically biased. If beliefs are overly pessimistic, this would imply that the world is in a state of pluralistic ignorance27, where systematic misperceptions about others’ WTC hinder cooperation and reinforce further pessimism. In such an equilibrium, correcting beliefs holds tremendous potential for fostering cooperation28,29,30,31.

The global survey

To obtain globally representative evidence on the willingness to act against climate change, we designed the Global Climate Change Survey. The survey was administered as part of the Gallup World Poll 2021/2022 in a large and diverse set of countries (N = 125) using a common sampling and survey methodology (Methods). The countries included in this study account for 96% of the world’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, 96% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 92% of the global population. To ensure national representativeness, each country sample is randomly selected from the resident population aged 15 and above. Interviews were conducted via telephone (common in high-income countries) or face to face (common in low-income countries), with randomly drawn phone numbers or addresses. Most country samples include approximately 1,000 respondents, and the global sample comprises a total of 129,902 individuals.

To assess respondents’ willingness to incur a cost to act against climate change, we elicit their willingness to contribute a fraction of their income to climate action. More specifically, we ask respondents whether they would be ‘willing to contribute 1% of [their] household income every month to fight global warming’ (answered yes or no), and, if not, whether they would be willing to contribute a smaller amount (yes or no). To account for the substantial variation in income levels across countries, the question is framed in relative terms. Respondents’ answers thus reflect how strongly they value climate action relative to alternative uses of their income. The figure of 1% is deliberately chosen as it falls within the range of plausible previously reported estimates of climate change mitigation costs32,33.

Our WTC measure has been empirically validated and shown to predict incentivized pro-climate donation decisions (Methods). In a representative US sample30, respondents who state they would be willing to contribute 1% of their monthly income donate 43% more money to a climate charity (P < 0.001 for a two-sided t-test, N = 1,993; Supplementary Fig. 1) and are 21–39 percentage points more likely to avoid fossil-fuel-based means of transport (car and plane), restrict their meat consumption, use renewable energy or adapt their shopping behaviour (all P < 0.001 for two-sided t-tests, N = 1,996; Supplementary Table 1).

To measure respondents’ beliefs about other people’s WTC, we first tell respondents that we are surveying many other individuals in their country about their willingness to contribute 1% of their household income every month to fight global warming. We then ask respondents to estimate how many out of 100 other individuals in their country would be willing to contribute this amount, that is, possible answers range from 0 to 100.

To assess individual approval of pro-climate social norms, we ask respondents to indicate whether they think that people in their country ‘should try to fight global warming’ (answered yes or no). Following recent research on social norms15,34, the item elicits respondents’ views about what other people should do, that is, what kind of behaviour they consider normatively appropriate (so-called injunctive norms10).

Finally, we measure demand for political action by asking respondents whether they think that their ‘national government should do more to fight global warming’ (answered yes or no). This item assesses the extent to which individuals regard their government’s current efforts as insufficient and sheds light on the potential for increased political action in the future.

The approval of pro-climate norms and the demand for political action are deliberately measured in a general manner to account for the fact that suitable concrete mitigation strategies may differ across countries. Our general measures strongly correlate with the approval of specific pro-climate norms and the demand for concrete policy measures (Methods). In a representative US sample, individuals who approve of the general norm to act against climate change are substantially more likely to state that individuals ‘should try to’ avoid fossil-fuel-based means of transport (car and plane), restrict their meat consumption, use renewable energy or adapt their shopping behaviour (correlation coefficients ρ between 0.35 and 0.51, all P < 0.001 for two-sided t-tests, N = 1,994; Supplementary Table 2). Similarly, the general demand for more political action is strongly correlated with demand for specific climate policies, such as a carbon tax on fossil fuels, regulatory limits on the CO2 emissions of coal-fired plants, or funding for research on renewable energy (ρ between 0.49 and 0.59, all P < 0.001 for two-sided t-tests, N = 1,996; Supplementary Table 3).

To ensure comparability across countries and cultures, professional translators translated the survey into the local languages following best practices in survey translation by using an elaborate multi-step translation procedure. The survey was extensively pre-tested in multiple countries of diverse cultural heritage to ensure that respondents with different cultural, economic and educational backgrounds could comprehend the questions in a comparable way. We deliberately refer to ‘global warming’ rather than ‘climate change’ throughout the survey to prevent confusion with seasonal changes in weather35,36, and provide all respondents with a brief definition of global warming to ensure a common understanding of the term.

A list of variables, definitions and sources is available in Methods. In all analyses, we use Gallup’s sampling weights, which were calculated by Gallup in multiple stages. A probability weight factor (base weight) was constructed to correct for unequal selection probabilities resulting from the stratified random sampling procedure. At the next step, the base weights were post-stratified to adjust for non-response and to match the weighted sample totals to known population statistics. The standard demographic variables used for post-stratification are age, gender, education and region. When describing the data at the supranational level, we also weight each country sample by its share of the world population.

Widespread global support for climate action

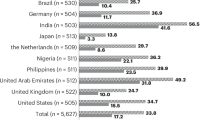

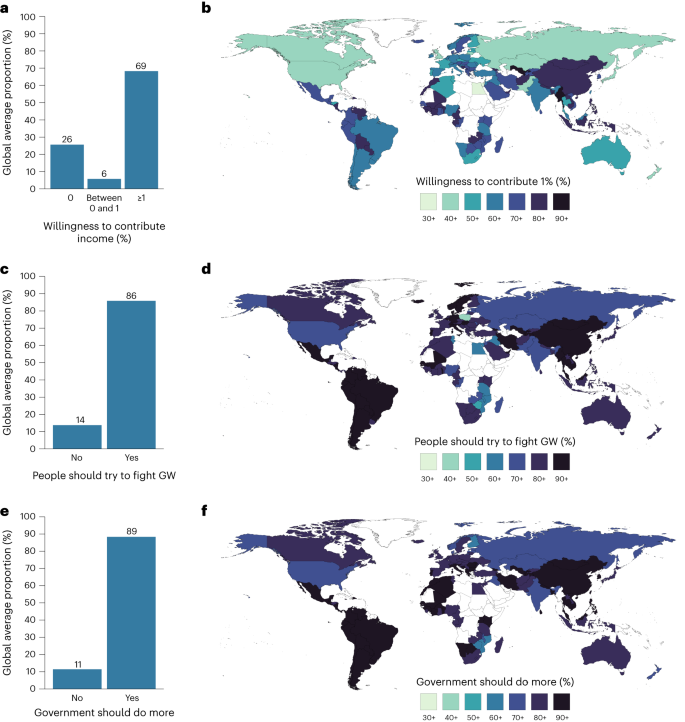

The globally representative data reveal strong support for climate action around the world. First, a large majority of individuals—69%—state they would be willing to contribute 1% of their household income every month to fight global warming (Fig. 1a). An additional 6% report they would be willing to contribute a smaller fraction of their income, and 26% state they would not be willing to contribute any amount. The proportion of respondents willing to contribute 1% of their income varies considerably across countries (Fig. 1b), ranging from 30% to 93%. In the vast majority of countries (114 of 125) the proportion is greater than 50%, and in a large number of countries (81 of 125) the proportion is greater than two-thirds.

a,c,e, The global average proportions of respondents willing to contribute income (a), approving of pro-climate social norms (c) and demanding political action (e). Population-adjusted weights are used to ensure representativeness at the global level. b,d,f, World maps in which each country is coloured according to its proportion of respondents willing to contribute 1% of income (b), approving of pro-climate social norms (d) and demanding political action (f). Sampling weights are used to account for the stratified sampling procedure. Supplementary Table 4 presents the data. GW, global warming.

Second, we document widespread approval of pro-climate social norms in almost all countries. Overall, 86% of respondents state that people in their country should try to fight global warming (Fig. 1c). In 119 of 125 countries, the proportion of supporters exceeds two-thirds (Fig. 1d).

Third, we identify an almost universal global demand for intensified political action. Across the globe, 89% of respondents state that their national government should do more to fight global warming (Fig. 1e). In more than half the countries in our sample, the demand for more government action exceeds 90% (Fig. 1f).

Stronger willingness to contribute in vulnerable countries

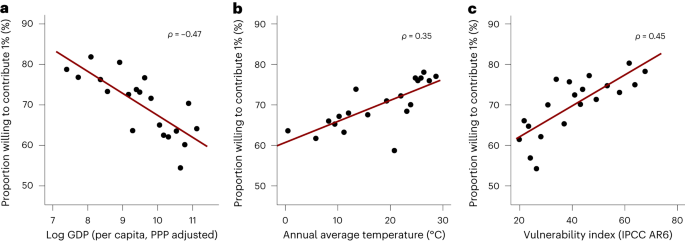

Although the approval of pro-climate social norms and the demand for intensified political action is substantial in almost all countries (Fig. 1d,f), there is considerable variation in the proportion of individuals willing to contribute 1% across countries (Fig. 1b) and world regions (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). What explains the cross-country variation in individual WTC? Two patterns stand out.

First, there is a negative relationship between country-level WTC and (log) GDP per capita (ρ = −0.47; 95% confidence interval (CI), [−0.60, −0.32]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t-test; N = 125; Fig. 2a). To illustrate, in the wealthiest quintile of countries, the average proportion of people willing to contribute 1% is 62%, whereas it is 78% in the least wealthy quintile of countries. A country’s GDP per capita reflects its resilience, that is, its economic capacity to cope with climate change. Put differently, in countries that are most resilient, individuals are least willing to contribute 1% of their income to climate action. At the same time, a country’s GDP is strongly related to its current dependence on GHG emissions37. For the countries studied here, the correlation coefficient between log GDP and log GHG emissions is 0.87. From a behavioural science perspective, this pattern is consistent with the interpretation that individuals are less willing to contribute if they perceive the adaptation costs as too high, that is, when the required lifestyle changes are perceived as too drastic.

a–c, Binned scatter plots of the country-level proportion of individuals willing to contribute 1% of their income and log average GDP (per capita, purchasing power parity (PPP) adjusted) for 2010–2019 (a), annual average temperature (°C) for 2010–2019 (b) and the vulnerability index used in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) (c)41,42. The vulnerability index ranges from 0 to 100, with higher values indicating higher vulnerability. Correlation coefficients are calculated from the unbinned country-level data. We use sampling weights to derive the country-level WTC. Number of bins, 20; 6–7 countries per bin; derived from x axis. The red line represents linear regression.

Second, we find a positive relationship between country-level WTC and country-level annual average temperature (ρ = 0.35; 95% CI, [0.18, 0.49]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t-test, N = 125; Fig. 2b). The average proportion of people who are willing to contribute increases from 64% among the coldest quintile of countries to 77% among the warmest quintile of countries. Average annual temperature captures how exposed a country is to global warming risks38,39. Countries with higher annual temperatures have already experienced greater damage due to global warming, potentially making future threats from climate change more salient to their residents40.

Both results replicate in a joint multivariate regression and are robust to the inclusion of continent fixed effects and other economic, political, cultural or geographic factors (Supplementary Tables 6–9). Focusing on North America, we also find a significantly positive association between WTC and average temperature on the subnational level (Supplementary Fig. 2). Moreover, as low GDP and high temperatures constitute two important aspects of vulnerability to climate change, we also draw on a more comprehensive summary measure of vulnerability, derived for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report41,42. In addition to national income and poverty levels, the index also takes into account non-economic factors, such as the quality of public infrastructure, health services and governance. It captures a country’s general lack of resilience and adaptive capacity, and it is highly correlated with log GDP (ρ = −0.93) and temperature (ρ = 0.62). Figure 2c confirms that people living in more vulnerable countries report a stronger WTC.

The country-level variation in pro-climate norms and demand for intensified political action is much smaller than that for the WTC. Nevertheless, we find that higher temperature predicts stronger norms and support for more political action. We do not detect a significant relationship with GDP (Supplementary Table 10).

Beliefs and systematic misperceptions

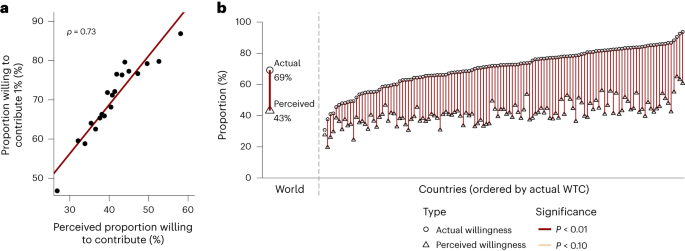

In line with previous research11,22,23,24,25,26, our data support the importance of conditional cooperation at the global level. Figure 3a shows a strong and positive correlation between the country-level proportions of individuals willing to contribute 1% and the corresponding average perceived proportions of fellow citizens willing to contribute 1% (ρ = 0.73; 95% CI, [0.64, 0.81]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t-test; N = 125).

a, Binned scatter plots of the country-level proportions of individuals willing to contribute 1% of their income and the average perceived proportions of others who are willing to contribute 1% of their income. We use sampling weights to derive the country-level WTC and perceived WTC. Number of bins, 20; 6–7 countries per bin; derived from x axis. The red line shows the linear regression. b, Gap between the global and country proportions of respondents who are willing to contribute 1% of their income (circles) and the global and country average perceived proportions of others willing to contribute (triangles). The reported significance levels result from two-sided t-tests testing whether the proportion of individuals who are willing to contribute is equal to the average perceived proportion. We use population-adjusted weights to derive the global averages and the standard sampling weights otherwise. We derive the averages based on all available data, that is, we exclude missing responses separately for each question. See Supplementary Figure 4 for additional descriptive statistics for the perceived WTC (median, 25–75% quartile range).

We document the same pattern at the individual level. In a univariate linear regression analysis, a 1-percentage-point increase in the perceived proportion of others’ WTC is associated with a 0.46-percentage-point increase in one’s own probability of contributing (95% CI, [0.41, 0.50]; P < 0.001; N = 111,134; Supplementary Table 11). This effect size aligns closely with the degree of conditional cooperation that has been documented in the laboratory26.

The critical role of beliefs raises the question of whether beliefs are well calibrated. In fact, Fig. 3b reveals sizeable and systematic global misperceptions. At the global level, there is a 26-percentage-point gap (95% CI, [25.6, 26.0]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t-test; N = 125; Supplementary Table 4) between the actual proportion of respondents who report being willing to contribute 1% of their income towards climate action (69%) and the average perceived proportion (43%). Put differently, individuals around the globe strongly underestimate their fellow citizens’ actual WTC to the common good. At the country level, the vast majority of respondents underestimate the actual proportion in their country (81%), and a large proportion of respondents underestimate the proportion by more than 10 percentage points (73%). This pattern holds for each country in our sample (Fig. 3b). In all 125 countries, the average perceived proportion is lower than the actual proportion, significantly so in all but one country (two-sided t-tests, actual versus perceived WTC). If we limit the analysis to those respondents for whom we have non-missing data for both the actual and the perceived WTC, the global perception gap is estimated to be 29 percentage points (95% CI, [27.2, 30.0]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t-test; N = 125; Supplementary Table 12), and the average perceived proportion is estimated to be significantly lower than the actual proportion in all 125 countries (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Although the perception gap is positive in all countries, we note that the size of the perception gap varies across countries (s.d. = 8.7 percentage points). Examining the same country-level characteristics as before, we find that the gap is significantly larger in countries with higher annual temperatures and significantly smaller in countries with high GDP (Supplementary Table 13). These results are largely robust to the inclusion of other economic, political or cultural factors, which we do not find to be significantly related to the perception gap. These findings are robust to only using respondents for whom we have non-missing data for both the actual and perceived WTC.

Discussion

Climate scientists have stressed that immediate, concerted and determined action against climate change is necessary32,41,43,44. Against this backdrop, our study sheds light on people’s willingness to contribute to climate action around the world. What sets our study apart from existing cross-cultural studies on climate change perceptions1,2,3,4 and policy views4,5,6 is its globally representative coverage and its behavioural science perspective.

The results are encouraging. About two-thirds of the global population report being willing to incur a personal cost to fight climate change, and the overwhelming majority demands political action and supports pro-climate norms. This indicates that the world is united in its normative judgement about climate change and the need to act.

The four aspects of cooperation discussed in this article are likely to interact with one another. For example, consensus on pro-climate norms is likely to strengthen individuals’ WTC and vice versa13. Similarly, the enactment of climate policies is likely to strengthen climate norms and vice versa45. We find a strong positive correlation between the WTC, pro-climate norms, policy support and beliefs about others’ WTC across countries (Supplementary Table 14). Moreover, countries with a stronger approval of pro-climate social norms have passed significantly more climate-change-related laws and policies (ρ = 0.20; 95% CI, [0.02, 0.36]; P = 0.028 for a two-sided t-test; N = 122). These positive interactions suggest that a change in one factor can unlock potent, self-reinforcing feedback cycles, triggering social-tipping dynamics46,47. Our findings can inform system dynamics models and social climate models that explicitly take into account the interaction of human behaviour with natural, physical systems48,49.

The widespread willingness to act against climate change stands in contrast to the prevailing global pessimism regarding others’ willingness to act. The world is in a state of pluralistic ignorance, which occurs when people systematically misperceive the beliefs or attitudes held by others27,28,29,30,31,50. The reasons underlying this perception gap are probably multifaceted, encompassing factors such as media and public debates disproportionately emphasizing climate-sceptical minority opinions51, and the influence of interest groups’ campaigning efforts52,53. Moreover, during periods of transition, individuals may erroneously attribute the inadequate progress in addressing climate change to a persistent lack of individual support for climate-friendly actions54.

Importantly, these systematic perception gaps can form an obstacle to climate action. The prevailing pessimism regarding others’ support for climate action can deter individuals from engaging in climate action, thereby confirming the negative beliefs held by others. Therefore, our results suggest a potentially powerful intervention, that is, a concerted political and communicative effort to correct these misperceptions. In light of a global perception gap of 26 percentage points (Fig. 3b) and the observation that a 1-percentage-point increase in the perceived proportion of others willing to contribute 1% is associated with a 0.46-percentage-point increase in one’s own probability to contribute (Supplementary Table 11), such an intervention may yield quantitatively large, positive effects. Rather than echoing the concerns of a vocal minority that opposes any form of climate action, we need to effectively communicate that the vast majority of people around the world are willing to act against climate change and expect their national government to act.

Methods

Sampling approach

The survey was carried out as part of the Gallup World Poll 2021/2022 in 125 countries, with a median total response duration of 30 min. The four questions were included towards the end of the Gallup World Poll survey and were timed to take about 1.5 min.

Each country sample is designed to be representative of the resident population aged 15 and above. The geographic coverage area from which the samples are drawn generally includes the entire country. Exceptions relate to areas where the safety of the surveyors could not be guaranteed or—in some countries—islands with a very small population.

Interviews are conducted in one of two modes: computer-assisted telephone interviews via landline or mobile phone or face to face (mostly computer assisted). Telephone interviews were used in countries with high telephone coverage, countries in which it is the customary survey methodology and countries in which the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic ruled out a face-to-face approach. There is one exception: paper-and-pencil interviews had to be used in Afghanistan for 73% of respondents to minimize security concerns.

The selection of respondents is probability based. The concrete procedure depends on the survey mode. More details are available in the documentation of the Gallup World Poll (https://news.gallup.com/poll/165404/world-poll-methodology.aspx)55.

Telephone interviews involved random-digit dialling or sampling from nationally representative lists of phone numbers. If contacted via landline, one household member aged 15 or older is randomly selected. In countries with a landline or mobile telephone coverage of less than 80%, this procedure is also adopted for mobile telephone calls to improve coverage.

For face-to-face interviews, primary sampling units are identified (cluster of households, stratified by population size or geography). Within those units, a random-route strategy is used to select households. Within the chosen households, respondents are randomly selected.

Each potential respondent is contacted at least three (for face-to-face interviews) or five (telephone) times. If the initially sampled respondent can not be interviewed, a substitution method is used. The median country-level response rate corresponds to 65% for face-to-face interviews and 9% for telephone interviews. These response rates are comparatively high considering that survey participants are not offered financial incentives for participating in the Gallup World Poll. For telephone interviews, the Pew Research Center reports a response rate of 6% in the United States in 2019 (https://pewrsr.ch/2XqxgTT). For face-to-face interviews, ref. 56 found a non-response rate of 23.7% even in a country with very high levels of trust, such as Denmark.

The median and most common sample size is 1,000 respondents. An overview of survey modes and sample sizes can be found in Supplementary Table 15.

Sampling weights

Although the sampling approach is probability based, some groups of respondents are more likely to be sampled by the sampling procedure. For instance, residents in larger households are less likely to be selected than residents in smaller households because both small and large households have an equal chance of being chosen. For this reason, Gallup constructs a probability weight factor (base weight) to correct for unequal selection probabilities. In a second step, the base weights are post-stratified to adjust for non-response and to match known population statistics. The standard demographic variables used for post-stratification are age, gender, education and region. In some countries, additional demographic information is used based on availability (for example, ethnicity or race in the United States). The weights range from 0.12 to 6.23, with a 10–90% quantile range of 0.28 to 2.10, ensuring that no observation is given an excessively disproportionate weight. Of all weights, 93% are between 0.25 and 4. More details are available in the documentation of the Gallup World Poll (https://news.gallup.com/poll/165404/world-poll-methodology.aspx)55.

We use these weights in our main analyses in two ways: first, when deriving national averages, we weight individual responses with Gallup’s sampling weights; and, second, when conducting individual-level regression analyses, we weight respondents with Gallup’s sampling weights.

We note that this weighting approach does not take into account the fact that some countries have a larger population than others. At the global level, the approach would effectively weight countries by their sample size and not their population size. Therefore, we also derive population-adjusted weights that render the data representative of the global population (aged ≥15) that is covered by our survey. The population-adjusted weight of individual i in country c is derived as

where wic denotes the original Gallup sampling weight, Ic the set of all respondents in country c, sc the country’s share of the global population aged ≥15 and n the total sample size of 129,902 respondents. Division by \({\sum }_{{I}_{c}}{w}_{ic}\) ensures that countries with a larger sample size (Supplementary Table 15) do not receive a larger weight. Multiplication with sc ensures that the total weight of a country sample is proportional to its population share. Multiplication with the constant n ensures that the total sum of the population-adjusted weights equals n, but is inconsequential for the results.

Although the two approaches yield very similar results (Supplementary Table 16), we use these population-adjusted weights wherever we present global statistics or statistics for supranational world regions. Supplementary Table 16 also shows that we obtain almost identical results if we do not use weights at all.

Global pre-test

A preliminary version of the survey was extensively pre-tested in 2020 in six countries of diverse cultural heritage—Colombia, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Kenya and Ukraine—to ensure that subjects from different cultural and economic backgrounds interpret the questions adequately. In each country, cognitive interviews were conducted by trained interviewers in local languages. The objectives of the pre-test were threefold, that is, to collect feedback, test whether the survey questions were understandable and check whether they were interpreted homogeneously across cultures. Each survey question was followed by additional probing questions that investigated respondents’ understanding of central terms and the overall logic of the question. Moreover, respondents were invited to express any comprehension difficulties. In response to the feedback, several minor adjustments to the survey were made. Most importantly, we switched to the term global warming instead of climate change to prevent confusion with seasonal changes in weather.

Survey items

The US English version of the questionnaire can be found below. Square brackets indicate information that is adjusted to each country. Parentheses indicate that a response option was available to the interviewer but not read aloud to the interviewee. The frequencies of missing data are summarized in Supplementary Table 17.

Introduction to global warming

Now, on a different topic… The following questions are about global warming. Global warming means that the world’s average temperature has considerably increased over the past 150 years and may increase more in the future.

Willingness to contribute

Question 1: Would you be willing to contribute 1% of your household income every month to fight global warming? This would mean that you would contribute [$1] for every [$100] of this income.

Responses: Yes, No, (DK), (Refused)

Coding: Binary dummy for Yes. (DK) and (Refused) are coded as missing data.

Question 2 (asked only if ‘No’ was selected in Question 1): Would you be willing to contribute a smaller amount than 1% of your household income every month to fight global warming?

Responses: Yes, No, I would not contribute any income, (DK), (Refused)

Coding: We classify respondents into three categories based on their responses to both questions. Willing to contribute (at least) 1%, willing to contribute between 0% and 1%, not willing to contribute. We conservatively code (DK) and (Refused) in Question 2 as ‘Not willing to contribute’.

Beliefs about others’ willingness to contribute

Question: We are asking these questions to 100 other respondents in [the United States]. How many do you think are willing to contribute at least 1% of their household income every month to fight global warming?

Responses: 0–100, (DK), (Refused)

Coding: 0–100, (DK) and (Refused) are coded as missing data.

Social norms

Question: Do you think that people in [the United States] should try to fight global warming?

Responses: Yes, No, (DK), (Refused)

Coding: Binary dummy for Yes. (DK) and (Refused) are coded as missing data.

Demand for political action

Question: Do you think the national government should do more to fight global warming?

Responses: Yes, No, (DK), (Refused)

Coding: Binary dummy for Yes. (DK) and (Refused) are coded as missing data.

Note: We were not allowed to field this question in Myanmar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Implementation errors

In two countries, an implementation error was made for the question on WTC a proportion of income.

In Kyrgyzstan, 4 of 1,001 respondents answered the survey in the language Uzbek. To these four respondents, the second sentence of question 1 was not read. The other respondents in Kyrgyzstan were interviewed in a different language and were not affected.

In Mongolia, respondents were asked whether they are willing to contribute less than 1% in question 1. Of these respondents, 93.1% answered yes. We approximate the proportion of Mongolian respondents who are willing to contribute 1% as follows. The implementation error should not affect the proportion of respondents who answer no to both questions (4.4%). Moreover, we know that in most countries 5–6% of respondents are not willing to contribute 1% but are willing to contribute a positive amount smaller than 1%. This is also true in neighbouring countries of Mongolia (China, 6.0%; Kazakhstan, 4.9%; Russia, 5.6%). Therefore, we derive the proportion of Mongolian respondents who are willing to contribute 1% as 100% − 4.4% − 6% = 89.6%, which is close to the uncorrected proportion of 93.1%. Results are virtually unchanged if we exclude observations from Mongolia.

Translation

The translation process of the US English original version into other languages followed the TRAPD model, first developed for the European Social Survey57. The acronym TRAPD stands for translation, review, adjudication, pre-testing and documentation. It is a team-based approach to translation and has been found to provide more reliable results than alternative procedures, such as back-translation. The following procedure is implemented:

-

Translation: a local professional translator conducts the first translation.

-

Review: the translation is reviewed by another professional translator from an independent company. The reviewer identifies any issues, suggests alternative wordings and explains their comments in English.

-

Adjudication: the original translator receives this feedback and can accept or reject the suggestions. In the latter case, he provides an English explanation for his decision and a third expert adjudicates the disputed translation, which often involves further exchange with the translators.

-

Pre-testing: a pilot test with at least ten respondents per language is conducted.

-

Documentation: translations and commentary (Gallup internal) are documented.

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Gallup World Poll. Informed consent was obtained from all human research participants.

Validation

Our main measures of support for climate action are deliberately measured in a general manner to account for the fact that suitable concrete strategies to act against climate change can differ widely across the globe. However, in previous work, we collected both the general measures and additional specific measures for the different facets of climate cooperation. We conducted a survey with a diverse sample of respondents that is representative of the US population in terms of the sociodemographic characteristics of age, gender, education and region30. Specifically, we first elicit respondents’ WTC, demand for political action and approval of pro-climate change norms. In a second step, respondents can allocate money between themselves and a pro-climate charity (incentivized). We also elicit whether respondents have engaged in a set of specific climate-friendly behaviours in the previous 12 months (answered yes or no). We further elicit whether they think that people in the United States should engage in these specific climate-friendly behaviours (yes or no). Finally, we measure support for specific climate-change-related policies and regulations using a four-point Likert scale. Supplementary Tables 1–3 show that our general measures are strongly correlated with concrete climate-friendly behaviours, concrete climate-friendly norms and support for specific climate-change-related policies and regulation. More details on these data can be found in ref. 30.

The data in ref. 30 also allow us to investigate whether we obtain similar results using two different survey methodologies. The Gallup World Poll relies on computer-assisted telephone interviews (landline and mobile) and random sampling via random-digit dialling. In ref. 30, an online survey was conducted and quota-based sampling was used. Reassuringly, we obtain very similar results for the proportion of the population willing to contribute 1% of their household income, supporting pro-climate norms and demanding more political action (Table 1).

Additional data sources

Annual temperature

This is the annual average temperature (in degrees Celsius) from 2010 to 2019. The data are available from the World Bank Group’s Climate Change Knowledge Portal (https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/download-data) and derived from the CRU TS v.4.05 data (https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/).

Continent

A set of indicators for whether a country belongs to one of the following five continents: (1) Africa, (2) Americas, (3) Asia, (4) Europe and (5) Oceania.

Economic growth

The average GDP growth rate between 2000 and 2019, obtained by averaging the year-on-year change in real GDP per capita (in constant US dollars) across years (World Bank WDI database, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators/Series/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.KD).

GDP

The average national GDP per capita from 2010 to 2019 in constant US dollars, adjusted for differences in purchasing power. To derive the percentage of world GDP that our survey represents, we take national GDP data from 2019. The data for each country are available from the World Bank WDI database (https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators/Series/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.KD). For Taiwan and Venezuela, the World Bank does not provide GDP estimates. Instead, we use data from the International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook Database (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2022/October).

GHG emissions

The per-capita GHG emissions expressed in equivalent metric tons of CO2 averaged from 2010 to 2019. To derive the percentage of world GHG emissions that our survey represents, we take national GHG data from 2019. GHGs include CO2 (fossil only), CH4, N2O and F gases. Data are obtained from EDGAR v.7.0 (ref. 58).

Individualism–collectivism

This refers to a country’s location on the individualism–collectivism spectrum, which we standardize59.

Kinship tightness

This refers to the extent to which people are embedded in large, interconnected extended family networks. The measure is derived from the data of the Ethnographic Atlas in ref. 60 and is available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/JX1OIU.

Regional temperature

The population-weighted regional mean temperature in degrees Celsius (between 2010 and 2019). Regions are defined by Gallup and often coincide with the first administrative unit below the national level. We use temperature data from the Climatic Research Unit (https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/) and population data from the LandScan database (https://www.ornl.gov/project/landscan) to construct this variable.

Scientific articles

The average number of scientific articles (per capita) from 2009 to 2018. The annual data for each country are available from the World Bank WDI database and normalized with annual population data from the Maddison Project Database 2020 (https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database-2020).

Secondary and tertiary education

This refers to the proportion of the population with secondary or tertiary education as the highest level of education. The Gallup World Poll includes respondent-level information on whether the highest level of educational attainment is secondary and tertiary education, which we aggregate to national proportion by using Gallup’s sampling weights.

Survival versus self-expression values

The extent to which people in a country hold survival versus self-expression values, which we standardize. We obtain the data from the axes of the Inglehart–Welzel Cultural Map (https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSNewsShow.jsp?ID=467)61.

Traditional versus secular values

The extent to which people in a country hold traditional versus secular values, which we standardize. We obtain the data from the axes of the Inglehart–Welzel Cultural Map (https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSNewsShow.jsp?ID=467)61.

Vulnerability index

This measure captures a country’s vulnerability as defined in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report41,42. Specifically, the measure is the average of the vulnerability subcomponent of the INFORM Risk Index and the WorldRiskIndex. The INFORM Risk Index consists of 32 indicators related to vulnerability and coping capacity. The vulnerability component of the WorldRiskIndex encompasses 23 indicators, which cover susceptibility, absence of coping ability and lack of adaptive capability. For example, the subcomponents include indicators of extreme poverty, food security, access to basic infrastructure, access to health care, health status and governance. The data and documentation are available at https://ipcc-browser.ipcc-data.org/browser/dataset?id=3736.

Quality of governance standard data set 2021

The following variables are compiled from the Quality of Governance Standard Data Set 2021 (https://www.gu.se/en/quality-government)62.

Concentration of political power

This variable is based on the Political Constraints Index III from the Political Constraint Index (POLCON) Dataset (https://mgmt.wharton.upenn.edu/faculty/heniszpolcon/polcondataset/), which we standardize.

Democracy

A binary measure of democracy, obtained from ref. 63.

Electricity from fossil fuels

The proportion of electricity produced from oil or coal (World Bank WDI database).

Perceived corruption

We use the Corruption Perception Index (0–100) from Transparency International (https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/), which we standardize.

Population

The size of the population aged 15 or higher in 2019. The data are taken from the World Bank WDI database.

Property rights

The standardized score of the degree to which a country’s laws protect private property rights and the degree to which those laws are enforced (Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom dataset; http://www.heritage.org/index/explore).

Quality of Governance Environmental Indicators Dataset 2021

The following variables are compiled from the Quality of Governance Environmental Indicators Dataset 2021 (https://www.gu.se/en/quality-government)64.

Annual precipitation

The long-run average of annual precipitation (in mm per year) (World Bank WDI database).

Climate change executive policies

The cumulative number of climate-change-related policies or other executive provisions (from 1946 until 2020), which were published or decreed by the government, president or an equivalent executive authority (https://climate-laws.org/)65.

Climate change laws and legislations

The cumulative number of climate-change-related laws and legislations (from 1946 until 2020) that were passed by the parliament or an equivalent legislative authority65.

Distance to coast

The average distance to the nearest ice-free coast (in 1,000 km)66.

Terrain ruggedness index

An index of the terrain ruggedness (as of 2012) originally developed to measure topographic variation67 and modified by ref. 66.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data of the Global Climate Change Survey are available at https://doi.org/10.15185/gccs.1. References to and the documentation of external and proprietary data, such as the Gallup World Poll data, are available in the Supplementary Information.

Code availability

The analysis code is available at https://doi.org/10.15185/gccs.1.

References

Capstick, S., Whitmarsh, L., Poortinga, W., Pidgeon, N. & Upham, P. International trends in public perceptions of climate change over the past quarter century. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 6, 35–61 (2015).

Eom, K., Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K. & Ishii, K. Cultural variability in the link between environmental concern and support for environmental action. Psychol. Sci. 27, 1331–1339 (2016).

Lee, T. M., Markowitz, E. M., Howe, P. D., Ko, C.-Y. & Leiserowitz, A. A. Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 1014–1020 (2015).

Leiserowitz, A. et al. International Public Opinion on Climate Change. (Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and Facebook Data for Good, 2021).

Dechezleprêtre, A. et al. Fighting Climate Change: International Attitudes toward Climate Policies. OECD Economics Department Working Paper 1714 (OECD Publishing, 2022).

Fabre, A., Douenne, T. & Mattauch, L. International Attitudes toward Global Policies. Berlin School of Economics Discussion Papers 22 (Berlin School of Economics, 2023).

Tam, K.-P. & Milfont, T. L. Towards cross-cultural environmental psychology: a state-of-the-art review and recommendations. J. Environ. Psychol. 71, 101474 (2020).

Cort, T. et al. Rising Leaders on Social and Environmental Sustainability. (Yale Center for Business and the Environment and Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, 2022).

Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 162, 1243–1248 (1968).

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R. & Kallgren, C. A. A focus theory of normative conduct: recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 58, 1015–1026 (1990).

Ostrom, E. Collective action and the evolution of social norms. J. Econ. Perspect. 14, 137–158 (2000).

Bicchieri, C. The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2006).

Nyborg, K. et al. Social norms as solutions. Science 354, 42–43 (2016).

Fehr, E. & Schurtenberger, I. Normative foundations of human cooperation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 458–468 (2018).

Constantino, S. M. et al. Scaling up change: a critical review and practical guide to harnessing social norms for climate action. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 23, 50–97 (2022).

Elster, J. Social norms and economic theory. J. Econ. Perspect. 3, 99–117 (1989).

Fehr, E. & Gächter, S. Cooperation and punishment in public goods experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 90, 980–994 (2000).

Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2015).

Dietz, T., Ostrom, E. & Stern, P. C. The struggle to govern the commons. Science 302, 1907–1912 (2003).

Besley, T. & Persson, T. The political economics of green transitions. Q. J. Econ. 138, 1863–1906 (2023).

Nowakowski, A. & Oswald, A. J. Do Europeans Care About Climate Change? An Illustration of the Importance of Data on Human Feelings. IZA Discussion Paper 13660 (IZA Institute of Labor Economics, 2020).

Fischbacher, U., Gächter, S. & Fehr, E. Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ. Lett. 71, 397–404 (2001).

Fehr, E. & Fischbacher, U. Social norms and human cooperation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 8, 185–190 (2004).

Gächter, S. in Economics and Psychology: A Promising New Cross-Disciplinary Field (eds Frey, B. S. & Stutzer, A.) Ch. 2 (MIT Press, 2007).

Rustagi, D., Engel, S. & Kosfeld, M. Conditional cooperation and costly monitoring explain success in forest commons management. Science 330, 961–965 (2010).

Gächter, S. in The Oxford Handbook of Behavioral Economics and the Law (eds Zamir, E. & Teichman, D.) 28–60 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2014).

Allport, F. H. Social Psychology (Houghton Mifflin, 1924).

Geiger, N. & Swim, J. Climate of silence: pluralistic ignorance as a barrier to climate change discussion. J. Environ. Psychol. 47, 79–90 (2016).

Mildenberger, M. & Tingley, D. Beliefs about climate beliefs: the importance of second-order opinions for climate politics. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 49, 1279–1307 (2019).

Andre, P., Boneva, T., Chopra, F. & Falk, A. Misperceived Social Norms and Willingness to Act Against Climate Change. ECONtribute Discussion Paper 101 (ECONtribute, 2022).

Sparkman, G., Geiger, N. & Weber, E. U. Americans experience a false social reality by underestimating popular climate policy support by nearly half. Nat. Commun. 13, 4779 (2022).

IPCC Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change (eds Shukla, P. R. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

Riahi, K. et al. The shared socioeconomic pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: an overview. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 153–168 (2017).

Bursztyn, L., González, A. L. & Yanagizawa-Drott, D. Misperceived social norms: women working outside the home in Saudi Arabia. Am. Econ. Rev. 110, 2297–3029 (2020).

Lorenzoni, I., Leiserowitz, A., de Franca Doria, M., Poortinga, W. & Pidgeon, N. F. Cross-national comparisons of image associations with ‘global warming’ and ‘climate change’ among laypeople in the United States of America and Great Britain. J. Risk Res. 9, 265–281 (2006).

Whitmarsh, L. What’s in a name? Commonalities and differences in public understanding of ‘climate change’ and ‘global warming’. Public Understand. Sci. 18, 401–420 (2009).

Azomahou, T., Laisney, F. & Nguyen Van, P. Economic development and CO2 emissions: a nonparametric panel approach. J. Public Econ. 90, 1347–1363 (2006).

Burke, M., Hsiang, S. M. & Miguel, E. Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 527, 235–239 (2015).

Diffenbaugh, N. S. & Burke, M. Global warming has increased global economic inequality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 9808–9813 (2019).

Zaval, L., Keenan, E. A., Johnson, E. J. & Weber, E. U. How warm days increase belief in global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 143–147 (2014).

IPCC Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (eds Pörtner, H.-O. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

Birkmann, J. et al. Understanding human vulnerability to climate change: a global perspective on index validation for adaptation planning. Sci. Total Environ. 803, 150065 (2022).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. et al. The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5°C. Science 365, eaaw6974 (2019).

IPCC Special Report on Global warming of 1.5°C (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Sunstein, C. R. On the expressive function of law. U. Pa. L. Rev. 144, 2021 (1996).

Milkoreit, M. et al. Defining tipping points for social–ecological systems scholarship—an interdisciplinary literature review. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 033005 (2018).

Otto, I. M. et al. Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth’s climate by 2050. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 2354–2365 (2020).

Beckage, B. et al. Linking models of human behaviour and climate alters projected climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 79–84 (2018).

Beckage, B., Moore, F. C. & Lacasse, K. Incorporating human behaviour into Earth system modelling. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 1493–1502 (2022).

Miller, D. T. & McFarland, C. Pluralistic ignorance: when similarity is interpreted as dissimilarity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 53, 298–305 (1987).

Boykoff, M. T. & Boykoff, J. M. Balance as bias: global warming and the US prestige press. Glob. Environ. Change 14, 125–136 (2004).

Oreskes, N. & Conway, E. M. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming (Bloomsbury, 2010).

Supran, G., Rahmstorf, S. & Oreskes, N. Assessing ExxonMobil’s global warming projections. Science 379, eabk0063 (2023).

Ross, L. The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: distortions in the attribution process. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 10, 173–220 (1977).

Worldwide Research: Methodology and Codebook (Gallup, 2021).

Christensen, A. I., Ekholm, O., Glümer, C. & Juel, K. Effect of survey mode on response patterns: comparison of face-to-face and self-administered modes in health surveys. Eur. J. Public Health 24, 327–332 (2013).

ESS Round 9 Translation Guidelines (European Social Survey, 2018).

Branco, A. et al. Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research, version v7.0_ft_2021 (European Commission, 2022).

Beugelsdijk, S. & Welzel, C. Dimensions and dynamics of national culture: synthesizing Hofstede with Inglehart. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 49, 1469–1505 (2018).

Enke, B. Kinship, cooperation, and the evolution of moral systems. Q. J. Econ. 134, 953–1019 (2019).

Inglehart, R. & Welzel, C. The Inglehart–Welzel world cultural map—World Values Survey 7. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/ (2023).

Teorell, J. et al. The Quality of Government Standard Dataset, version Jan22 (Univ. of Gothenburg: The Quality of Government Institute, 2022).

Boix, C., Miller, M. & Rosato, S. Boix–Miller–Rosato dichotomous coding of democracy, 1800–2015. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FJLMKT (Harvard Dataverse, 2018).

Povitkina, M., Alvarado Pachon, N. & Dalli, C. M. The Quality of Government Environmental Indicators Dataset, version Sep21 (Univ. of Gothenburg: The Quality of Government Institute, 2021).

Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment & Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. Climate Change Laws of the World Database. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/legislation (2021).

Nunn, N. & Puga, D. Ruggedness: the blessing of bad geography in Africa. Rev. Econ. Stat. 94, 20–36 (2012).

Riley, S. J., DeGloria, S. D. & Elliot, R. A terrain ruggedness index that quantifies topographic heterogeneity. Intermt. J. Sci. 5, 23–27 (1999).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Gächter, I. Haaland, L. Henkel, A. Oswald, C. Roth, E. Weber and J. Wohlfart for valuable comments. We thank M. Antony for his support in collecting and managing the Global Climate Change Survey data, and J. König, L. Michels, T. Reinheimer and U. Zamindii for excellent research assistance. Funding by the Institute on Behavior and Inequality (briq) (A.F.) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; through Excellence Strategy EXC 2126/1 390838866 (P.A., T.B. and A.F.) and through CRC TR 224) is gratefully acknowledged (P.A. and A.F.). The activities of the Center for Economic Behavior and Inequality (CEBI) are financed by the Danish National Research Foundation, grant DNRF134 (F.C.). We gratefully acknowledge research support from the Leibniz Institute for Financial Research SAFE (P.A.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (P.A., T.B., F.C. and A.F.) contributed equally to all activities, including the design of the survey, data analysis and writing of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Kimin Eom, Adrien Fabre and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–4 and Tables 1–17.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Andre, P., Boneva, T., Chopra, F. et al. Globally representative evidence on the actual and perceived support for climate action. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 253–259 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-01925-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-01925-3